Norwegian Mountain Salmon (NMS) are the company behind plans for a 90,000 ton mega farm drilled into a hill in Scotland. Here in an English-language exclusive they go through their plans for their 26,000-ton pilot project on the Norwegian island of Utsira.

On the tiny island of Utsira, a small Norwegian municipality with just 200 residents, an ambitious project is taking shape that could revolutionise the way the world thinks about salmon farming.

Spearheaded by Norwegian Mountain Salmon (NMS) and its general manager, Bård Hjelmen, the initiative aims to produce 125 million salmon portions annually from a facility that blends seamlessly into the natural landscape.

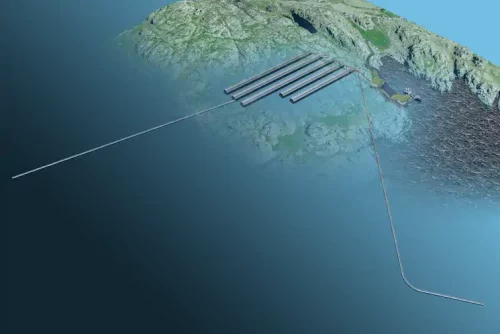

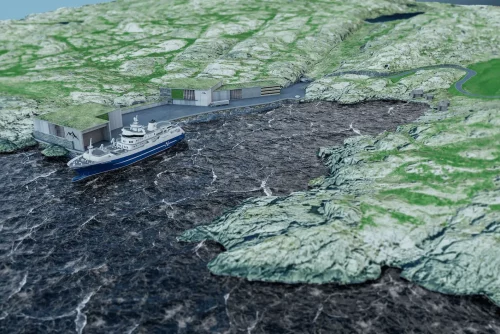

Nestled within the rock outcroppings of Utsira, located 11 miles west of the Norwegian mainland, NMS intends to construct a state-of-the-art flow-through facility comprising 72 tanks. These tanks will harness seawater pumped from 50 meters below the surface, west of Utsira, promising an eco-friendly approach to salmon farming free from the usual concerns about lice, antibiotics, and adverse weather conditions.

The scale of the project is impressive: NMS is targeting a production capacity of 26,000 metric tons.

Although this ambition hinges on the Norwegian government reopening applications for land-based aquaculture permits. (In December 2022, the country’s Ministry of Trade and Fisheries introduced a moratorium on applications for permits for land-based aquaculture, which was to apply until new regulations for land-based aquaculture were in place. The suspension has now stretched over one year and two months.)

Nevertheless, Hjelmen’s enthusiasm is palpable as he envisions the impact of this project, not just for Utsira, but for sustainable food production worldwide: ‘I don’t know of a place with so few inhabitants (200) that produces so much food,’ Hjelmen tells iLaks’ Tina Totland Jenssen.

The total price is estimated at NOK 2.4 billion ($230 million). And the company anticipates a profit after tax of NOK 532 million ($50.6 million) annually once the facility is fully operational, with a return on invested equity after four years. However, they will keep their footprint small:

“We are in favor of a 90 percent reduced visible footprint compared to comparable facilities,” says Hjelmen.

For its part, Utsira municipality welcomes the project – which could potentially create 60 jobs and provide up to NOK 10 million ($1 million) in extra tax revenue for the municipality. But they would not have been as positive about large, visible buildings, according to local head of industry, environment and technology, Erik Hørlück Berg.

“This is one of the most precious coastal landscapes we have. So you would probably never have been allowed to build anything in the surface,” says Berg.

Norwegian Mountain Salmon has chosen Utsira for several reasons: Among other things, the steady supply of fresh seawater for flow through, and the absence of other aquaculture site. Apart from Mowi, which has been granted permission to operate on the opposite side of the island, there are no other farms nearby.

“The gold in the project is the clean, infection-free water – and a good recipient,” says municipal director May Britt Jensen. “The location on Utsira gives minimal risk of infection to and from other fish. Each pool will be its own biological zone, with a separate supply of water, so that infection from one pool to another will not be possible,” explains William Vossgård, who is project manager for technology at NMS.

The proposed plant is expected to produce an annual output of 80,000 tons of sludge annually, containing seven percent dry matter. If this sludge were dried to a dry matter content of 25-35 percent, the estimated annual costs for shipping and delivery could hit up to NOK 60 million ($6 million). This process would also necessitate about eight tanker trips daily, significantly increasing NMS’s environmental impact on the island.

Concerns regarding the potential negative effects, including odor and the need for large sludge silos at the quay, were discussed with the local municipality. Recognizing these issues, Hjelmen expressed the need for an alternative solution to manage the sludge in a more environmentally friendly and efficient manner.

The preferred solution identified by NMS is to establish a smaller-scale pyrolysis plant. This plant would be compact enough to fit within the area, generate its own energy, and importantly, reduce the sludge discharge by approximately 70 percent. This approach aims to mitigate the environmental impact while addressing the logistical challenges associated with the plant’s operation.

The process devised by Norwegian Green Tech for handling fish sludge involves a heating technique that transforms the sludge into synthetic gas, biochar, and heat. Adiam Negassie from Norwegian Green Tech explains that before undergoing pyrolysis, the sludge is first dried to achieve 80 percent dry matter content. From the initial 80,000 tonnes of sludge, the process results in approximately 1,200 tonnes of biochar.

This biochar has multiple potential uses, including soil improvement, fertilizer or compost creation, and water purification. A key advantage of this method is that it leaves no bioresidual waste; all materials are converted into useful products, thereby creating a local circular value chain. Furthermore, biochar has the distinctive ability to store carbon, making it a beneficial tool in combating global warming. This innovative approach also addresses the significant logistical challenges associated with managing large volumes of sludge.

The management of sludge at the plant has been a crucial factor in gaining approval from the municipality. Municipal manager Berg acknowledges that there was initial skepticism among the public, as this method of sludge handling is a novel approach that has rarely been attempted before. A key concern addressed by this approach is the avoidance of frequent transportation of sludge across the island, which would have required numerous lorries, thereby reducing the potential environmental and infrastructural impact on the local community.

“I believe that if Norway is to succeed as a farming nation, one must think holistically when choosing a location,” says Hjelmen. He believes that Norway is particularly well equipped for flow-through facilities.

“RAS can be built anywhere. But we have to make arrangements for the comparative advantages we have, use all technology – and use technology where it has the best prerequisites for success,” he says.

Alfred Bjørlo (parliamentary representative for the Liberal Party and member of the Business Committee) is also out to Kvalvikvågen. He agrees with Hjelmen’s statement about making use of comparative advantages. – This type of facility that we see here is not the whole solution for future farming, but I think it is part of the solution, says Bjørlo.

On what scale do you think we can have land-based facilities along the coast?

“There are great advantages to producing on land, but in the long run it is not possible to imagine that we can use more and more large areas and spread out along the coast. I think it will be impossible to do that on a large scale, for many reasons, Bjørlo replies.