Some producers might feel tempted to trumpet the findings of Compassion in World Farming’s new welfare scorecard but they should show solidarity and shun it.

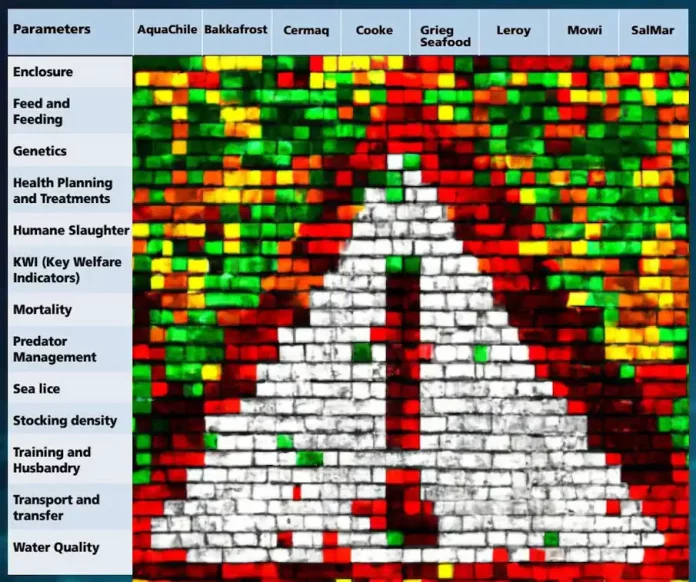

Earlier this week, UK-based lobbying group Compassion in World Farming’s (CIWF) released a welfare score card grading major salmon producers on criteria including stocking density, humane harvest, sea lice infestations and mortality.

The eight salmon producers evaluated – AquaChile, Bakkafrost, Cermaq, Cooke, Grieg Seafood, Leroy, Mowi, and SalMar – represent more than 50 percent of worldwide salmon production.

While the initiative is commendable for its focus on salmon welfare, its inadequate research dramatically oversimplifies the complexity of salmon farming, with dangerous implications for the industry.

Dangers of oversimplification

Oversimplifying complex problems can lead to confusion for consumers that has the potential to damage the entire industry. For instance, a ranking system might score producers based on sea lice infestation rates (outside farmers’ control) without considering the producer’s investment in environmentally friendly lice treatment methods (inside their control).

This speaks to a one-size-fits-all approach, but the truth is that different regions have different environmental conditions and challenges. A salmon farm in Norway, for instance, faces different ecological and regulatory environments compared to a farm in Iceland, let alone Chile, making a universal ranking system potentially inaccurate or unfair.

What’s more, rankings that focus primarily on negative aspects can overlook the positive steps a producer has taken, such as investments in sustainable feed or habitat restoration efforts. This can lead to a skewed perception of a producer’s overall sustainability practices.

Standardized criteria?

Another issue is the lack of standardized criteria. Different producers may have varying criteria for sustainability, with one prioritizing low carbon footprints while another might focus on local ecosystem impacts.

To take an example from another industry, this problem was evident when the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program red-listed American lobster based on concerns about the impact of fishing practices on the endangered North Atlantic right whales.

The lobster industry in Maine argued that their practices had become increasingly sustainable (including the removal of over 27,000 miles of floating rope, and the use of breakaway links designed to free entangled whales) but the blanket red-listing by Seafood Watch failed to acknowledge these efforts.

While Seafood Watch focused on the potential threat to right whales, local stakeholders and industry groups highlighted their ongoing efforts to mitigate these risks and the lack of recent incidents linking their practices to whale endangerment.

This case exemplifies the challenges posed by a lack of standardised sustainability criteria across different organisations.

Or what about in 2021, when the same organisation downgraded British Columbia’s farmed Atlantic salmon to the “Avoid” category? The downgrade was based on factors like the use of antimicrobials and pesticides. Seafood Watch reported that while half of the BC farms didn’t use any antimicrobials from 2018-2020, the other half used them multiple times a year. The ranking generalised the practices of all BC farms based on the practices of some, potentially misrepresenting those farms that employed better management practices. How then can companies operating up and down thousands of miles of coastline, across multiple continents be accurately judged?

Transparency:

One of the biggest issues is that producers may choose not to publicly disclose detailed data on their farming practices, making it challenging for ranking organisations to accurately assess their operations.

As Cooke VP Joel Richardson wrote: “No credible seafood sustainability organisation assesses and ranks both publicly traded and privately owned companies based on a cursory review of their website content. But that’s what CIWF does in their scheme – which is why Cooke does not participate in their ranking.”

Reluctance to share highly sensitive data should not be used by pressure groups to whack companies over the head, as is clearly the case in the CIWF rankings where Cooke are shown as in the red for every criteria bar one.

Laudable aims

While CIWF’s effort to promote higher welfare standards in salmon farming is laudable, a more comprehensive, nuanced, and collaborative approach could be more effective. Such an approach would recognise the strides made in the industry while still holding it accountable for continuous improvement.

This score card, in its current form, risks placing undue emphasis on single vague aspects of welfare, potentially overlooking other critical elements such as environmental sustainability, technological innovation, and the socio-economic benefits of an industry that employs thousands, often in remote and hard to access areas.

Some producers may be inclined to celebrate their favourable ratings in Compassion in World Farming’s welfare scorecard, but it would be more prudent for them to stand in unity with the industry and distance themselves from endorsing it.

With the world’s fisheries facing significant pressures, and some nearing the brink of collapse, the shift to sustainable aquaculture becomes increasingly crucial.

Allowing a third party such scope to misrepresent responsible producers with overly broad or inaccurate assessments would be a serious misstep. It not only undermines the efforts of responsible producers but also hinders the progress towards a more sustainable future.